|

Visit the Historic Photo Gallery, to see these photos and more

California

is called the "Golden State" possibly for many reasons,

among which, and in addition to its abundant sunshine, is the

exciting and colorful history of the Gold Rush.

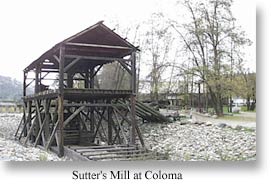

Along the Mother Lode Highway 49 on the way to Coloma, among the flowering white dogwoods, olive colored oaks and towering cedar, there are remnants of this history: old stone cabins and buildings, mining equipment, and stamp mills that were used to crush gold-bearing quartz.

On

an icy cold morning early in 1848, James Wilson Marshall, a carpenter

from New Jersey, picked up a few nuggets of gold from the American

River at the site of a sawmill he was building for John Sutter

near Coloma. By August, the hills above the river were strewn

with wood huts and tents as the first of 4,000 miners lured by

the gold discovery scrambled to strike it rich. Prospectors, from

the East sailed around Cape Horn. Some hiked across the Isthmus

of Panama, and by 1849, about 40,000 came to San Franciso by sea

alone. Nearly $2,000,000,000 in gold was taken from the earth

before mining became dormant. On

an icy cold morning early in 1848, James Wilson Marshall, a carpenter

from New Jersey, picked up a few nuggets of gold from the American

River at the site of a sawmill he was building for John Sutter

near Coloma. By August, the hills above the river were strewn

with wood huts and tents as the first of 4,000 miners lured by

the gold discovery scrambled to strike it rich. Prospectors, from

the East sailed around Cape Horn. Some hiked across the Isthmus

of Panama, and by 1849, about 40,000 came to San Franciso by sea

alone. Nearly $2,000,000,000 in gold was taken from the earth

before mining became dormant.

The upheaval was enormous. Native American cultures that had lasted for thousands of years in California were lost and destroyed. But the Mormon economy in Utah flourished with the large gold riches funneled into their banks. The old Mexican province suddenly became a new state. The gold that enriched California may have even precipitated the Civil War.

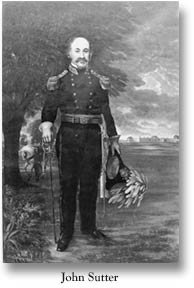

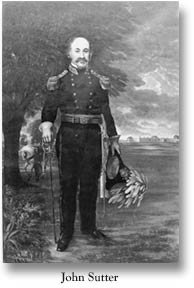

James Marshall was building the sawmill to supply lumber for Sutter's Fort in the Sacramento Valley. John Sutter had ambitious dreams of creating an empire--the New Helvetia in the Sacramento Valley. But his great fiefdom was destroyed because all of his holdings and Sutter's Fort were lost to the ever-increasing masses seizing everything in pursuit of instant wealth.

Because the gold discovery was such a large historical event and affected so many different people, there followed a vast number of conflicting stories about how and who was responsible for the exact way in which it occurred. Several tales include one report from a Mrs. Wimmer, the cook, who claims her husband was a co-discoverer and that the precious yellow metal was found by her children. The Mormons reportedly got wind of it through Henry Bigler's friends working on a new sawmill near Sutter's Fort. They later came to Coloma and prospected at a spot that became the rich diggings of Mormon Island. More than $80,000 eventually went through Brigham Young's gold accounts and into the Mormon mint in 1848-1851.

The date that Marshall found those first few flakes in the tailrace of the sawmill is uncertain. Today most historians agree that Marshall was the discoverer, and that the date was January 24.

Marshall was not on a gold hunting expedition

that icy Monday morning when he shut off the water. He and his

crew were building a sawmill. The tailrace was too shallow to

carry water fast enough past the wheel that powered the saw. They

needed to dig the tailrace during the day and to let water pour

through at night to scour the bottom which then turned the ditch

into a giant sluice box with cracks that exposed bedrock serving

as the rifles which caught the gold that washed from the loosened

gravel of the banks. By early morning, Marshall walked down the

tailrace below the mill wheel and found in a crevice in the smooth

granite bedrock, under water, those flakes of the raw yellow,

and at first, thought it was Blotite, or "fools gold."

The gold, wrapped in a handkerchief, he took to Sutter where they looked up in Sutter's well-worn encyclopedia whatever they could find on the subject of gold, and then they tested the sample in nitric acid from Sutter's medical kit. It was almost pure gold.

John Sutter decided they should be cautious. Henry Bigler had been keeping a diary in which he reported that within only a few days the men at the mill had done a little prospecting on their own and had picked up more than $100 worth of gold. Sutter worried that "easy" gold would make it difficult to get men to work. He needed workers to build the gristmill to grind his flour, and for constructing other farming facilities that would make his empire--the New Helvetia--profitable. Sutter and Marshall had no legal claim to the Coloma area, nor to the land on which the mill was located. Sutter negotiated an agreement with the Indians in exchange for a promise of clothing and other items. However, the U. S. military governor in Monterey, Colonel Richard B. Mason, refused to accept it. Mason maintained that the Indians had no title to the land. According to him, it belonged to the United States by right of conquer. John Sutter decided they should be cautious. Henry Bigler had been keeping a diary in which he reported that within only a few days the men at the mill had done a little prospecting on their own and had picked up more than $100 worth of gold. Sutter worried that "easy" gold would make it difficult to get men to work. He needed workers to build the gristmill to grind his flour, and for constructing other farming facilities that would make his empire--the New Helvetia--profitable. Sutter and Marshall had no legal claim to the Coloma area, nor to the land on which the mill was located. Sutter negotiated an agreement with the Indians in exchange for a promise of clothing and other items. However, the U. S. military governor in Monterey, Colonel Richard B. Mason, refused to accept it. Mason maintained that the Indians had no title to the land. According to him, it belonged to the United States by right of conquer.

In the beginning, both Sutter and Marshall tried to keep the discovery a secret. But word got out when Jacob Wittmer took two wagons up to the mill on February 9 and the Wimmer children told him all about the gold. He brought the news back to the fort store, flashing the gold, and the store operator sent word to his partner, Sam Brannan, in San Francisco. Sutter, himself, was soon telling visitors to the fort about the discovery, and the first newspaper, the Californian, had a small item about it on March 15 with the headline, "GOLD MINE FOUND. Sam Brannan's rival paper, California Star, followed with more brief mention of the discovery. Charles Bennett who had been present at the discovery and remembered pounding out one of the pieces on an anvil himself, was sent to Monterey to bring the news to governor, Colonel Mason.

At first there was little more than a few curiosity

seekers. Many assumed it was a hoax. Henry Bigler continued to

work the mill only on Sundays and holidays, the times Marshall

would allow. Soon visitors from the fort and the gristmill, and

men from the scattered Sacramento Valley ranches began to come

to do a little "prospecting." Isaac Humphrey came up

to the mill from San Francisco on April 1 with his friend Bennett,

bringing the first piece of mining equipment: a rocker.

The

news did spread. More and more, people were getting gold fever.

Sam Brannan, who had come by ship to San Francisco with a following

of Mormon settlers, met with his partner at the Sutter's Fort

store and went on to Mormon Island where the Mormon miners showed

him their gold, and gave him the Church's tithe. While in San

Francisco, Brannan, was shouting everywhere, "Gold! Gold!

Gold from the American River!" It is reported that within

a few days the town was nearly emptied. The

news did spread. More and more, people were getting gold fever.

Sam Brannan, who had come by ship to San Francisco with a following

of Mormon settlers, met with his partner at the Sutter's Fort

store and went on to Mormon Island where the Mormon miners showed

him their gold, and gave him the Church's tithe. While in San

Francisco, Brannan, was shouting everywhere, "Gold! Gold!

Gold from the American River!" It is reported that within

a few days the town was nearly emptied.

Sutter's agricultural enterprises began to fall apart. He got his wheat harvested, but there was no one to thrash it. The stone wheels of his grist mill never produced any flour. Hides rotted in his tannery vats. Squatters settled in brush shelters in his fields and vandalized the fort itself, stealing, according to Sutter, even the bells from his fort.

Colonel Richard B. Mason, as the military governor of California, came to Coloma, after first celebrating the Fourth of July with John Sutter at Sutter's Fort. Together, he and his adjutant, Lt. William Tecumseh Sherman of later Civil War fame, gathered information and estimated that about 4000 people were working the mines, about half of whom were Indians, and that some $30,000 to $50,000 worth of gold was being mined every day. Mason toured the area with James Marshall and actually saw quantities of gold, fourteen pounds of which had been taken from the North Fork the previous week by Indians working for John Sinclair, one of Sutter's neighbors.

By July, the gold discovery had reached Hawaii. By August, the news had reached Oregon, and soon people began arriving from the ranches and towns of Southern California, Sonora, and provinces of northern Mexico. Rapidly, word was reaching even such faraway places as Chili and Peru.

At the close of 1848, high water ended the first mining season, but there were approximately 5,000 miners still working, and new strikes were being made every day.

When Colonel Mason's report reached Washington, accompanied by a tea caddy full of Gold, President Polk sent a message about the Gold out West to Congress on December 5. Editorials began warning against the "folly" of rushing out to California to get rich.

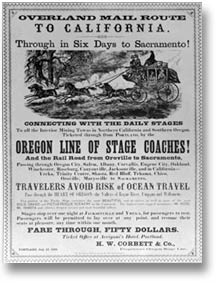

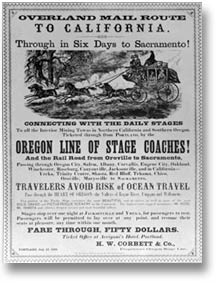

But they came. And they came. Englanders came on anything that would float. Sometimes taking five months to round Cape Horn to get to San Francisco. They came from Michigan, Ohio, and western Pennsylvania. Miners from Georgia took the Santa Fe Trail and routes across Mexico. Those with money came by steamer to Panama, then by dugout and mule to the Pacific side of the isthmus for another steamer to San Francisco. By the end of 1849 there were 40,000 people in the mines. Disillusionment settled in because of growing problems with lawlessness and sickness.

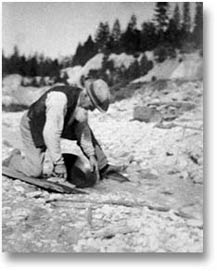

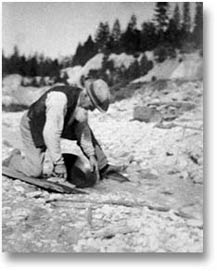

Mining evolved from pocketknife to the gold pan, from the pan to the rocker, and the rocker to the long tom and the sluice box.

By the fall of '49 gold fever had spread worldwide. Companies were being formed in Great Britain, Germany, and France. Miners were recruited from China. The Gold Rush assuaged some of the grievances of the economic world problems: the potato famine in Ireland; revolution in France, Germany, and Italy; Taiping Rebellion and opium wars in China. The California Gold Rush by the end of 1850 had affected markets worldwide.

After 1850 major engineering efforts were required, because most of the remaining big gold deposits were under rivers or in prehistoric riverbeds. Hard-rock mining involved miles of tunnels beneath the earth and was followed in later times by hydraulic mining which washed away whole mountainsides. The hydraulic mining muddied up the riverbeds so badly that they became unnavigable. In 1882 the old steamer, Daisy, made its last run up the American River to the town of Folsom. On the Sacramento, Marysville was no longer a port. Farmlands were flooded and buried under sand, mud, and rocks. Still, miners continued to try and recover as much of the last few bits of gold as they could find. Inevitably, there followed long environmental battles over the use of giant dredgers that left endless windrows of bare stones. Early during World War II, all gold mining in the United States was stopped by executive order. By the time the presidential order was lifted, the old gold mining gear had rusted or been sold for scrap. Today, recreational panners and suction-dredge operators in scuba gear rework the creeks and rivers, reminiscent of the early '49er days. After 1850 major engineering efforts were required, because most of the remaining big gold deposits were under rivers or in prehistoric riverbeds. Hard-rock mining involved miles of tunnels beneath the earth and was followed in later times by hydraulic mining which washed away whole mountainsides. The hydraulic mining muddied up the riverbeds so badly that they became unnavigable. In 1882 the old steamer, Daisy, made its last run up the American River to the town of Folsom. On the Sacramento, Marysville was no longer a port. Farmlands were flooded and buried under sand, mud, and rocks. Still, miners continued to try and recover as much of the last few bits of gold as they could find. Inevitably, there followed long environmental battles over the use of giant dredgers that left endless windrows of bare stones. Early during World War II, all gold mining in the United States was stopped by executive order. By the time the presidential order was lifted, the old gold mining gear had rusted or been sold for scrap. Today, recreational panners and suction-dredge operators in scuba gear rework the creeks and rivers, reminiscent of the early '49er days.

By the fall of 1848 there were still only three stores in Coloma. One of them was Sam Brannan's. Coloma Valley had once been described as a "beautiful hollow surrounded on all sides by lofty mountains." Eventually the hundreds of scrubby tents and shanties that covered the hillsides around Marshall's rough cabins gave way to more substantial buildings. Coloma became the hub of the northern mining region in the early fifties and soon had opulent hotels and restaurants, becoming the county seat serving a surrounding population of several thousand. Tens of thousands more passed through.

It became a thriving Gold Rush town with only 600 to 900 residents, even though its placers could only support a modest number of gold-seekers.

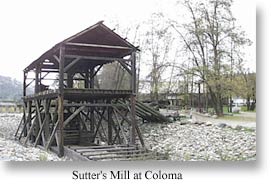

In the May 13, 1854 edition of The Empire County Argus, Sutter's Mill was heralded as being part of the "first page of our history." And it continued with, "The accidental discovery of gold at Sutter's Mill was a commencement of a new era in the affairs of the world."

Although John Sutter tried desperately to find ways to profit from the discovery, both he and John Marshall never enjoyed the wealth, power, and prestige they felt they deserved. But what they set in motion was something far greater than either of them ever envisioned. Although John Sutter tried desperately to find ways to profit from the discovery, both he and John Marshall never enjoyed the wealth, power, and prestige they felt they deserved. But what they set in motion was something far greater than either of them ever envisioned.

Today you can visit the town that became known as the "Queen of the Mines," and tour the Marshall Gold Discovery State Historic Park. You can see James Marshall's cabin, and when you think of all that gold, it is sobering to look at this cabin and realize that throughout his life, he never lived in anything very much fancier. On one side of the highway close beside the river you can see a working replica of Sutter's mill and think of the thwarted little Swiss empire--the New Helvetia that was John Sutter's dream. Or you can look to the skyline to the southwest through a carefully cut break in the trees and see James Marshall's statue pointing to the spot where he found the first flake of gold glistening in the sun.

|

California State Parks

California State Capitol Museum

The park is located downtown Sacramento

at 10th and L Streets. 916-324-0333

California State Railroad Museum

The park is located in Old Sacramento at

125 "I" Street. 916-445-7387

Columbia State Historic Park

The park is three miles north of Sonora,

off Highway 49. 209-532-0150

Empire Mine State Historic Park

The park is located in Grass Valley at 10791

East Empire Street. 530-273-8522

Leland Stanford Mansion

State Historic Park

Malakoff Diggins State Historic Park

Marshall Gold Discovery

State Historic Park

Hwy 49, Coloma, CA - 916-445-4422

Old Sacramento State Historic Park

Railtown 1897 State Historic Park

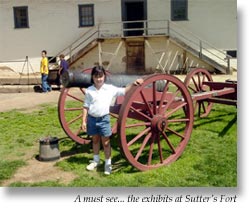

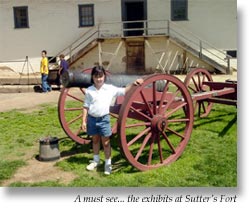

Sutter's Fort State Historic Park

2701 L. Street, Sacramento, CA - 916-445-4422

State Indian Museum

2618 K Street, Sacramento - 916-324-0971

www.parks.ca.gov

|

|

For a more diverse

look at California History we recommend you visit California

1850, A snapshot in time!

click

on the book at left |

|

For history

of the gold mines between Downieville and Sierra city

click on the book at left |

|

On

an icy cold morning early in 1848, James Wilson Marshall, a carpenter

from New Jersey, picked up a few nuggets of gold from the American

River at the site of a sawmill he was building for John Sutter

near Coloma. By August, the hills above the river were strewn

with wood huts and tents as the first of 4,000 miners lured by

the gold discovery scrambled to strike it rich. Prospectors, from

the East sailed around Cape Horn. Some hiked across the Isthmus

of Panama, and by 1849, about 40,000 came to San Franciso by sea

alone. Nearly $2,000,000,000 in gold was taken from the earth

before mining became dormant.

On

an icy cold morning early in 1848, James Wilson Marshall, a carpenter

from New Jersey, picked up a few nuggets of gold from the American

River at the site of a sawmill he was building for John Sutter

near Coloma. By August, the hills above the river were strewn

with wood huts and tents as the first of 4,000 miners lured by

the gold discovery scrambled to strike it rich. Prospectors, from

the East sailed around Cape Horn. Some hiked across the Isthmus

of Panama, and by 1849, about 40,000 came to San Franciso by sea

alone. Nearly $2,000,000,000 in gold was taken from the earth

before mining became dormant. John Sutter decided they should be cautious. Henry Bigler had been keeping a diary in which he reported that within only a few days the men at the mill had done a little prospecting on their own and had picked up more than $100 worth of gold. Sutter worried that "easy" gold would make it difficult to get men to work. He needed workers to build the gristmill to grind his flour, and for constructing other farming facilities that would make his empire--the New Helvetia--profitable. Sutter and Marshall had no legal claim to the Coloma area, nor to the land on which the mill was located. Sutter negotiated an agreement with the Indians in exchange for a promise of clothing and other items. However, the U. S. military governor in Monterey, Colonel Richard B. Mason, refused to accept it. Mason maintained that the Indians had no title to the land. According to him, it belonged to the United States by right of conquer.

John Sutter decided they should be cautious. Henry Bigler had been keeping a diary in which he reported that within only a few days the men at the mill had done a little prospecting on their own and had picked up more than $100 worth of gold. Sutter worried that "easy" gold would make it difficult to get men to work. He needed workers to build the gristmill to grind his flour, and for constructing other farming facilities that would make his empire--the New Helvetia--profitable. Sutter and Marshall had no legal claim to the Coloma area, nor to the land on which the mill was located. Sutter negotiated an agreement with the Indians in exchange for a promise of clothing and other items. However, the U. S. military governor in Monterey, Colonel Richard B. Mason, refused to accept it. Mason maintained that the Indians had no title to the land. According to him, it belonged to the United States by right of conquer. The

news did spread. More and more, people were getting gold fever.

Sam Brannan, who had come by ship to San Francisco with a following

of Mormon settlers, met with his partner at the Sutter's Fort

store and went on to Mormon Island where the Mormon miners showed

him their gold, and gave him the Church's tithe. While in San

Francisco, Brannan, was shouting everywhere, "Gold! Gold!

Gold from the American River!" It is reported that within

a few days the town was nearly emptied.

The

news did spread. More and more, people were getting gold fever.

Sam Brannan, who had come by ship to San Francisco with a following

of Mormon settlers, met with his partner at the Sutter's Fort

store and went on to Mormon Island where the Mormon miners showed

him their gold, and gave him the Church's tithe. While in San

Francisco, Brannan, was shouting everywhere, "Gold! Gold!

Gold from the American River!" It is reported that within

a few days the town was nearly emptied.

After 1850 major engineering efforts were required, because most of the remaining big gold deposits were under rivers or in prehistoric riverbeds. Hard-rock mining involved miles of tunnels beneath the earth and was followed in later times by hydraulic mining which washed away whole mountainsides. The hydraulic mining muddied up the riverbeds so badly that they became unnavigable. In 1882 the old steamer, Daisy, made its last run up the American River to the town of Folsom. On the Sacramento, Marysville was no longer a port. Farmlands were flooded and buried under sand, mud, and rocks. Still, miners continued to try and recover as much of the last few bits of gold as they could find. Inevitably, there followed long environmental battles over the use of giant dredgers that left endless windrows of bare stones. Early during World War II, all gold mining in the United States was stopped by executive order. By the time the presidential order was lifted, the old gold mining gear had rusted or been sold for scrap. Today, recreational panners and suction-dredge operators in scuba gear rework the creeks and rivers, reminiscent of the early '49er days.

After 1850 major engineering efforts were required, because most of the remaining big gold deposits were under rivers or in prehistoric riverbeds. Hard-rock mining involved miles of tunnels beneath the earth and was followed in later times by hydraulic mining which washed away whole mountainsides. The hydraulic mining muddied up the riverbeds so badly that they became unnavigable. In 1882 the old steamer, Daisy, made its last run up the American River to the town of Folsom. On the Sacramento, Marysville was no longer a port. Farmlands were flooded and buried under sand, mud, and rocks. Still, miners continued to try and recover as much of the last few bits of gold as they could find. Inevitably, there followed long environmental battles over the use of giant dredgers that left endless windrows of bare stones. Early during World War II, all gold mining in the United States was stopped by executive order. By the time the presidential order was lifted, the old gold mining gear had rusted or been sold for scrap. Today, recreational panners and suction-dredge operators in scuba gear rework the creeks and rivers, reminiscent of the early '49er days. Although John Sutter tried desperately to find ways to profit from the discovery, both he and John Marshall never enjoyed the wealth, power, and prestige they felt they deserved. But what they set in motion was something far greater than either of them ever envisioned.

Although John Sutter tried desperately to find ways to profit from the discovery, both he and John Marshall never enjoyed the wealth, power, and prestige they felt they deserved. But what they set in motion was something far greater than either of them ever envisioned.