The

Intrepid Females of Forty-Nine

JoAnn

Levy

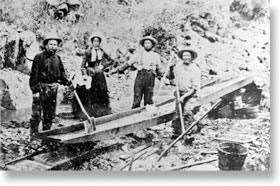

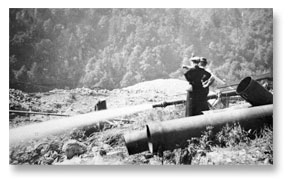

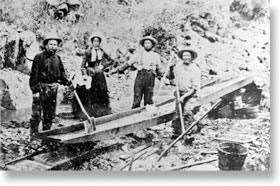

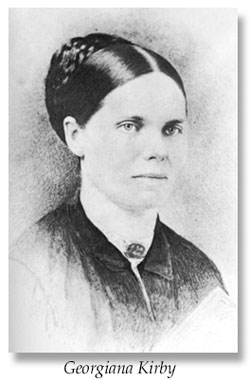

Note, historic

photos are randomly placed and are not associated with

any person or persons in this article. The two actresses: Lola

Montez, and Lotta Crabtree are correctly depicted.

In

1849, by conservative estimates, 25,000 people crossed the plains

to California . The number arriving that year by sea, from around

the Horn and across the Isthmus, exceeded 30,000 . This immense

migration traveling beneath the canvas of covered wagons and

the canvas of sails included many surprisingly adventurous women.

One

of them was Mary Jane Megquier who crossed the Isthmus early

in 1849, and wrote this of her Chagres River journey:

One

of them was Mary Jane Megquier who crossed the Isthmus early

in 1849, and wrote this of her Chagres River journey:

“The birds singing monkeys screeching the Americans laughing

and joking the natives grunting as they pushed us along through

the rapids was enough to drive one mad with delight.”

She cheerfully described the sights, including the church at

Gorgona, which was “overrun with domestic animals in time

of service…. A mule took the liberty to depart this life

within its walls while we were there, which was looked upon

by the natives of no consequence.”

Mrs. Megquier took to travel like a duck to water. On

a later trip, after visiting family in Maine, she returned to

San Francisco via Nicaragua, without her husband, but in company

with two women. She breezily wrote from Nicaragua:

“We spent three days very pleasantly although all were

nearly starved for the want of wholesome food but you know my

stomach is not lined with pink satin the bristles on the pork,

the weavels in the rice and worms in the bread did not start

me at all, but I grew fat upon it. Emily, Miss Bartlett and

myself had a small room with scarce light enough to see the

rats and spiders…”

Lucilla Brown, a more critical traveler, crossed the Isthmus

late in 1849, in a company that included “seven females.”

She intentionally did not write ladies, “for all do not

deserve the name.”

Among those acceptable to her was John Sutter’s

family. Since they were Swiss, Mrs. Brown could converse little

with them, but of the remaining women passengers Mrs. Brown

had decided opinions:

“There is a Mrs. Brayner, an upholsterer by trade, going

on to meet her husband in San Francisco. A Miss Scott, about

fifty years old, going independent and alone, to speculate in

California – of course, no very agreeable person. Then

there is a Mrs. Taylor, whose husband left her some years ago—is

said to have a father in California, whither she purports to

be bound. She is young and has some pretentions to beauty, and

at first commanded sympathy and attention from the gentlemen;

but they all left her except the keeper of the hotel at Chagres,

a low fellow, who retains her at his lodgings there, and it

is to be hoped she will proceed no further.”

Women who crossed to California by land also noted the presence

of other women. Catherine Haun, whose party took the Lassen

route in 1849, wrote that her caravan had “a good many

women and children.”

Among forty-niners traveling the southern route through present-day

New Mexico and Arizona into San Diego was a woman with the wonderful

name of Louisiana Strentzel, who met eight families in just

one party on this road.

No stranger to gold fever, Mrs. Strentzel wrote from San Diego

to her family back home that the latest news from the mines

was that “gold is found in 27-pound lumps.” She

also wrote that her husband hadn’t been sick a day since

they left, and their two children were red and rosy and outgrowing

their clothes. She, herself, she wrote, never enjoyed better

health in her life.

Good health was noted by many women on the trails, who enjoyed

the invigorating exercise.

|

Lola

Montez

Eliza Rosanna Gilbert, born in Grange, County Sligo, Ireland

on February 17, 1821 was better known by her stage name

Lola Montez. the Irish-born dancer and actress

became famous as the mistress of King Ludwig I of Bavaria.

In 1846, she traveled to Munich, where she was discovered

by Ludwig I of Bavaria. Ludwig made her Countess of Landsfeld.

During the Bavarians’ revolt, Ludwig abdicated, and

Lola fled Bavaria for the United States.

From 1851 to 1853 she performed as a dancer and actress

in the eastern United States, then moved to San Francisco

in May 1853, where she married Patrick Hull and moved to

Grass Valley, California.

Lola contracted pneumonia and passed away on January 17,

1861, one month short of her fortieth birthday. |

Others noted

the novelty of the landscape, like Harriet Ward, a grandmother:

“The scenery through which we are constantly passing is

so wild and magnificently grand that it elevates the soul from

earth to heaven and causes such an elasticity of mind that I

forget I am old.”

And Lucena Parsons wrote in her diary:

“At the bottom of this valley are some very singular rocks.

It appears sublime to me to see these rocks towering one above

the other & lifting their majestick heads here in this solitary

spot. Oh, beautiful is the hand of nature.”

Lucena’s

journal was not otherwise a happy record. Lucena was a grave

counter. Few of her journal entries failed to mention at least

one. In all, she counted more than 380 graves while crossing

the plains. So commonplace was the face of death by the time

her party reached Fort Laramie that she sandwiches mention of

it casually between other observations:

Lucena’s

journal was not otherwise a happy record. Lucena was a grave

counter. Few of her journal entries failed to mention at least

one. In all, she counted more than 380 graves while crossing

the plains. So commonplace was the face of death by the time

her party reached Fort Laramie that she sandwiches mention of

it casually between other observations:

“It seems like home again to meet so many on the road.

We did not look for it in this wild country. I found the skull

of a man by the roadside. I took it on & buried it at the

point. There is a blacksmiths shop here for the accomodation

of emigrants kept by a French man.”

Death was far less a casual matter by the time overlanders reached

the dreaded desert. The especial cruelty of the long trek west

was that the easy part came first. The rolling grasslands of

the prairies, encountered in the springtime when people and

stock were fresh, should have come last, not mountains to climb

when food, animals, and spirit were exhausted. These mountains,

the rugged Sierra Nevada, formed the final obstacle to California’s

golden promises. They took their toll in wagons smashed and

abandoned. There were accidents. But, unless trapped by snow,

emigrants had little fear of failing to cross the Sierra. Not

so, the hot, dry 40-mile gauntlet of desert lying between the

Humbolt River and the Carson or Truckee rivers flowing from

the eastern Sierra.

By the time overlanders approached this final desert, they and

their animals had plodded and slogged and climbed and descended

nearly 2,000 miles. In a meadow near the Humboldt River’s

sink, the travel-weary emigrants cut grass for their worn and

thin mules and oxen, dried as much as they could carry, and

hurried on. There was no forage on the desert’s final

40 miles

Few passages of women’s diaries and letters are

more poignant than those recording this desert crossing. Sallie

Hester’s 1849 diary entry is eloquent testimony to the

hardship:

“Stopped and cut grass for the cattle and supplied ourselves

with water for the desert. Had a trying time crossing. Several

of our cattle gave out, and we left one. Our journey through

the desert was from Monday, three o’clock in the afternoon,

until Thursday morning at sunrise, September 6. The weary journey

last night, the mooing of the cattle for water, their exhausted

condition, with the cry of “Another ox down,” the

stopping of the train to unyoke the poor dying brute, to let

him follow at will or stop by the wayside and die, and the weary,

weary tramp of men and beasts, worn out with heat and famished

for water, will never be erased from my memory. Just at dawn,

in the distance, we had a glimpse of the Truckee River, and

with it the feeling: Saved at last!”

Another 49er

family, Josiah and Sarah Royce, with their two-year-old daughter

Mary, crossed the Carson River in October. To avoid the heat,

they traveled the desert at night. In the dark, they missed

the fork to the meadows and its precious grass. Far upon the

desert, they realized the mistake. Sarah’s recollection

of that moment never faded:

“So there was nothing to be done but turn back and try

to find the meadows. Turn back! What a chill the words sent

through one. Turn back, on a journey like that; in which every

mile had been gained by most earnest labor, growing more and

more intense, until, of late, it had seemed that the certainty

of advance with every step was all that made the next step possible.

And now, for miles, we were to go back. In all that long journey

no steps ever seemed so heavy, so hard to take, as those with

which I turned my back to the sun that afternoon of October

4, 1849.”

Most overland emigrants on the California Trail kept to the

tried and true Carson and Truckee routes, but every rumor of

a faster, easier way found an ear anxious to believe. At the

Humboldt especially, with the dreaded desert ahead and the high

mountains beyond, even the most conservative travelers considered

a convincingly proposed alternative. In 1849, thousands succumbed

to the temptation. Either through argument or the example of

the wagon ahead, much of the tail end of that year’s migration

turned north from the Humbolt for Peter Lassen’s ranch.

They succeeded only in exchanging one desert for another, while

adding 200 desperate and dangerous miles to their journey—traveling

north nearly to the Oregon border.

|

Lotta

Crabtree

Charlotte Mignon Crabtree was born

in 1847 in New York City to parents John Ashworth Crabtree

and Mary Ann (Livesey) Crabtree. In 1851, her father left

for San Francisco looking for gold, Lotta and her mother

followed in 1852. The family reunited in Grass Valley, California

to run a boarding house for the miners.

It was here, Lotta met actress Lola Montez and became her

protégé. Lotta made her first professional

appearance at a tavern owned by Matt Taylor. Lotta began

traveling to all of the mining camps performing ballads

and dancing for the miners. In 1856, the family moved back

to San Francisco where Lotta toured Sacramento and the Valley,

and became frequently in demand. By 1859 she had become

"Miss Lotta, the San Francisco Favorite".

Lotta retired in 1891. The profits from her career, wisely

invested in real estate all over the country during her

tours, allowed her to lead a comfortable life. At her death

in 1924 she left an estate of four million dollars. |

Catherine

Haun’s party took that road. She remembered well the hardships

“The alkali dust of this territory

was suffocating, irritating our throats and clouds of it often

blinded us. The mirages tantalized us; the water was unfit to

drink or use in any way; animals often perished or were so overcome

by heat and exhaustion that they had to be abandoned, or in

case of human hunger, the poor jaded creatures were killed and

eaten…. One of our dogs was so emaciated and exhausted

that we were obliged to leave him on this desert and it was

said that the train following us used him for food.”

No one can measure the fear and suffering endured by these people

on the Lassen route, or by those on the desert crossings to

the Truckee and Carson rivers, or on the southern trail into

San Diego. But the fear and suffering of emigrants on another

route into California could not have been surpassed.

In October of 1849, from a camp south of Salt Lake City, more

than 300 people followed Jefferson Hunt, a guide familiar with

the Old Spanish Trail to Los Angeles. A pack train overtook

them, and in it was a man with a map showing a cutoff from this

trail. The tantalizing prospect of short-cut immediately danced

in the minds of impatient emigrants. The temptation was too

much for a Methodist minister named John Brier, who fired others

with his zeal for the cutoff. Although Jefferson Hunt refused

to take it, on November 4, 1849, approximately 27 wagons did.

Among them were four families, including the Briers. Their path

took them into a vast and desolate desert, a hellhole they would

name Death Valley.

Thirty-four men, mostly young and mostly from Illinois, calling

themselves Jayhawkers, entered the desert valley. Three of them

died there. The Rev. Mr. Brier, his wife Juliet, and their three

young sons followed the Jayhawkers in a desperate search for

a way out.

When

one young man suggested to Juliet that she and her children

remain behind and let them send back for her, she adamantly

refused:

When

one young man suggested to Juliet that she and her children

remain behind and let them send back for her, she adamantly

refused:

“I knew what was in his mind.

“No,” I said, “I have never been a hindrance,

I have never kept the company waiting, neither have my children,

and every step I take will be toward California.” Give

up! I knew what that meant: a shallow grave in the sand.”

Juliet Brier earned the Jayhawkers’ great respect and

affection, one recalling that in walking nearly a hundred miles

through sand and sharp-edged rocks that she frequently carried

one of her children on her back, another in her arms, and held

the third by the hand. At Jayhawker reunions she was spoken

of as a heroine for caring for the sick among them.

Her own recollection was modest:

“Did I nurse the sick? Ah, there

was little of that to do. I always did what I could for the

poor fellows, but that wasn’t much. When one grew sick

he just lay down, weary like, and his life went out. It was

nature giving up. Poor souls!”

Care

for her own family consumed most of Juliet’s strength.

In one 48-hour stretch without water, her oldest boy Kirk suffered

terribly:

Care

for her own family consumed most of Juliet’s strength.

In one 48-hour stretch without water, her oldest boy Kirk suffered

terribly:

“The child would murmur occasionally,

“Oh, father, where’s the water?” His pitiful,

delirious wails were worse than the killing thirst. It was terrible.

I seem to see it all over again. I staggered and struggled wearily

behind with the other two boys and the oxen. The little fellows

bore up bravely and hardly complained, though they could barely

talk, so dry and swollen were their lips and tongue. John would

try to cheer up his brother Kirk by telling him of the wonderful

water we would find and all the good things we could get to

eat. Every step I expected to sink down and die.”

The Brier family, with much suffering, reached safety on February

12, 1850. The other three families lost in Death Valley also

survived. The Wade family celebrated deliverance on February

10. The Bennett and Arcan families, heroically rescued by two

selfless young men, escaped the valley of death on March 7….four

months and three days after their fateful decision to take the

cutoff.

The Brier family made a home in Marysville, the Wades in Alviso,

the Bennetts at Moss Landing, and the Arcans in Santa Cruz.

Captivated by the beautiful redwoods there, Abigail Arcan announced

to her husband: “You can go to the mines if you want to.

I have seen all the godforsaken country I am going to see, and

I’m going to stay right here as long as I live.”

And she did. Her first necessity, of course, like all women

new to California, was a home. California offered few comforts,

however, and almost nothing homelike.

Forty-niner

Anne Booth came around the Horn in a ship she continued to live

aboard for more than a month in San Francisco’s Bay, and

wrote:

Forty-niner

Anne Booth came around the Horn in a ship she continued to live

aboard for more than a month in San Francisco’s Bay, and

wrote:

“…it is true, there are

many disadvantages and privations attending life in California;

but these I came prepared to encounter, and by no means expected

to find the comforts and refinements of home….”

In mining camps, many forty-niner women continued to live in

the wagons that brought them, which Mrs. John Berry found “very

disagreeable.”

“The rains set in early in November, and continued with

little interruption until the latter part of March and here

were we poor souls living almost out of doors. Sometimes of

a morning I would come out of the wagon and find the…shed

under which I cooked blown over & my utensils lying in all

directions, fire out & it pouring down as tho’ the

clouds had burst. Sometimes I would scold and fret, other times

endure it in mute agony…”

And how she yearned for a comfortable bed

“Oh! you who lounge on your divans

& sofas, sleep on your fine, luxurious beds…know nothing

of the life of a California emigrant. Here are we sitting on

a pine block…sleeping in beds with either a quilt or a

blanket as substitute for sheets (I can tell you it is very

aristocratic to have a bed at all)”….

In towns, of course, were hotels – if one stretched the

definition. The celebrated St. Francis Hotel of San Francisco

opened in 1849 and was so high class even then that it boasted

it offered sheets on its beds. No other hotel did.

A

reminiscence of a lady guest from those early days confirms

that her bed there was “delightful.” Two “soft

hair mattresses” and “a pile of snowy blankets”

hastened her slumbers, which were soon interrupted:

A

reminiscence of a lady guest from those early days confirms

that her bed there was “delightful.” Two “soft

hair mattresses” and “a pile of snowy blankets”

hastened her slumbers, which were soon interrupted:

“I was suddenly awakened by voices,

as I thought, in my room; but which I soon discovered came from

two gentlemen, one on each side of me, who were talking to each

other from their own rooms through mine; which, as the walls

were only of canvas and paper, they could easily do. This was

rather a startling discovery, and I at once began to cough,

to give them notice of my interposition, lest I should become

an unwilling auditor of matters not intended for my ear. The

conversation ceased, but before I was able to compose myself

to sleep again…a nasal serenade commenced, which, sometimes

a duet and sometimes a solo, frightened sleep from my eyes….”

A 49er woman living in Santa Cruz knew about thin walls, too.

She was Eliza Farnham, a widow who had come round the Horn with

two children and a woman friend to claim property left by Eliza’s

late husband.

She described the ‘casa’ she inherited on

her Santa Cruz ranch, as:

“Not a cheerful specimen, even

of California habitations—being made of slabs, were originally

placed upright, but which have departed sadly from the perpendicular

in every direction….”

Mrs. Farnham focused her initial housekeeping wants on simply

getting a stove installed. During the three-day period that

Eliza called the ‘siege of the stove,’ a hired man

failed at the task, as did her friend Miss Sampson. Then Eliza

tackled it:

“On the third day, it was agreed that stoves could not

have been used in the time of Job, or all his other afflictions

would have been unnecessary.”

Not

afraid of labor, Mrs. Farnham set herself the task of building

a new house:

Not

afraid of labor, Mrs. Farnham set herself the task of building

a new house:

“My first participation in the

labor of its erection was the tenanting of the joists and studding

for the lower story, a work in which I succeeded so well, that

during its progress I laughed, when I paused for a few moments

to rest, at the idea of promising to pay a man $14 or $16 per

day for doing what I found my own hands so dexterous in.”

Eliza Farnham, who conquered a stove, built a house, and put

her Santa Cruz land to growing potatoes, quickly recognized

that women in California would have to work.

And indeed 49er women did work. Some even mined. A newspaper

editor saw a woman at Angel’s Creek dipping and pouring

water into the gold washer her husband rocked. The editor reported

that she wore short boots, white duck pantaloons, a red flannel

shirt, with a black leather belt and a Panama hat.

Louise Clappe tried her hand at digging gold, too:

“I have become a mineress; that

is, if the having washed a pan of dirt with my own hands, and

procured therefrom three dollars and twenty-five cents in gold

dust…will entitle me to the name. I can truly say, with

the blacksmith’s apprentice at the close of his first

day’s work at the anvil, ‘I am sorry I learned the

trade;’ for I wet my feet, tore my dress, spoilt a pair

of new gloves, nearly froze my fingers, got an awful headache,

took cold and lost a valuable breastpin, in this my labor of

love.”

An easier and more profitable avenue to gold, for most women,

was the selling of familiar domestic skills, like Abby Mansur’s

neighbor at Horseshoe Bar: “she makes from 15 to 20 dollars

a week washing…has all she wants to do so you can see

that women stand as good chance as men.”

Mary Jane Caples made pies

“My venture was a success. I sold

fruit pies for one dollar and a quarter a piece, and mince pies

for one dollar and fifty cents. I sometimes made and sold a

hundred in a day, and not even a stove to bake them in, but

had two small dutch ovens.”

One woman boasted:

“I have made about $18,000 worth

of pies—about one third of this has been clear profit.

One year I dragged my own wood off the mountain and chopped

it, and I have never had so much as a child to take a step for

me in this country. $11,000 I baked in one little iron skillet,

a considerable portion by a campfire, without the shelter of

a tree from the broiling sun.”

Another woman wrote, from San Francisco

“A smart woman can do very well

in this country—true, there are not many comforts and

one must work all the time and work hard, but there is plenty

to do and good pay. If I was in Boston now and know what I now

know of California I would come out here – if I had to

hire the money to bring me out. It is the only country I ever

was in where a woman received anything like a just compensation

for work.”

Running a boardinghouse was the commonest money-maker

for women. One woman earned $189 a week after only three weeks

of keeping boarders in the mines. She shared with her boarders

accommodations decidedly minimal, as she wrote her children

back East:

“We have one small room about

14 feet square, and a little back room we use for a storeroom

about as large as a piece of chalk. Then we have an open chamber…

divided off by a cloth. The gentlemen occupy one end, Mrs. H

and daughter, your father and myself, the other. We have a curtain

hung between our beds but we do not take pains to draw it, as

it is of no use to be particular here.”

Luzena Wilson set herself up in the boardinghouse business,

too. Despite its rustic beginnings, she had grand plans for

her Nevada City enterprise, which she elevated with the title

‘hotel’:

“I bought two boards from a precious

pile belonging to a man who was building the second wooden house

in town. With my own hands I chopped stakes, drove them into

the ground, and set up my table. I bought provisions at a neighboring

store, and when my husband came back at night he found 20 miners

eating at my table. Each man as he rose put a dollar in my hand

and said I might count him a permanent customer. I called my

hotel ‘El Dorado.’”

But running a boardinghouse was hard work, as Mary Jane

Megquier attested from San Francisco:

“I should like to give you an

account of my work if I could do it justice. I get up and make

the coffee, then I make the biscuit, then I fry the potatoes

and broil 3 pounds of steak, and as much liver, while the hired

woman is sweeping and setting the table. At 8 the bell rings

and they are eating until nine. I do not sit until they are

nearly all done…after breakfast I bake 6 loaves of bread

(not very big) then 4 pies or a pudding, then we have lamb,

for which we have paid $9 a quarter, beef, pork, baked turnips,

beets, potatoes, radishes, salad, and that everlasting soup,

every day, dine at 2, for tea we have hash, cold meat, bread

and butter, sauce and some kind of cake and I have cooked every

mouthful that has been eaten excepting one day when we were

on a steamboat excursion. I make 6 beds every day and do the

washing and ironing and you must think I am very busy and when

I dance all night I am obliged to trot all day and if I had

not the constitution of 6 horses I should have been dead long

ago but I am going to give up in the fall, as I am sick and

tired of work.”

In full agreement was Mary Ballou, who kept a boardinghouse

in the mines. Her complaints included the additional inconvenience

of unwelcome animals.

“Anything can walk into the kitchen and then from the

kitchen into the dining room so you see the hogs and mules can

walk in any time, day or night, if they choose to do so. Sometimes

I am up all times a night scaring the hogs and mules out of

the house. I made a blueberry pudding today for dinner. Sometimes

I am making soups and cranberry tarts and baking chicken that

cost $4 a head and cooking eggs at $3 a dozen. Sometimes boiling

cabbage and turnips and frying fritters and broiling steak and

cooking codfish and potatoes. Sometimes I am taking care of

babies and nursing at the rate of $50 a week but I would not

advise any Lady to come out here and suffer the toil and fatigue

that I have suffered for the sake of a little gold.”

One

woman determined to get her gold the old-fashioned way, by marrying

it. She placed what must have been the first personals ad in

a California newspaper, under the head:

A Husband Wanted...

By a lady who can wash, cook, scour, sew, milk, spin, weave,

hoe (can’t plow), cut wood, make fires, feed the pigs,

raise chickens, rock the cradle, (gold rocker, I thank you,

Sir!), saw a plank, drive nails, etc. These are a few of the

solid branches; now for the ornamental. “long time ago”

she went as far as syntax, read Murray’s Geography and

through two rules in Pike’s Grammar. Could find 6 states

on the atlas. Could read, and you can see that she can write.

Can—no, could—paint roses, butterflies, ships, etc.

Could once dance; can ride a horse, donkey or oxen…Oh,

I hear you ask, could she scold? No, she can’t you _____________good-for-nothing

_________!

Now for her terms. Her age is none of your business. She is

neither handsome nor a fright, yet an old man need not apply,

nor any who have not a little more education than she has, and

a great deal more gold, for there must be $20,000 settled on

her before she will bind herself to perform all the above. Address

to Dorothy Scraggs, with real name. P.O. Marysville.”

Of course there were all kinds of ways

women could earn a ‘little gold,’ and they did.

Catherine Sinclair managed a theatre. A French woman barbered.

Julia Shannon took photographs. Sophia Eastman was a nurse.

Mrs. Pelton taught school. Mrs. Phelps sold milk. Mary Ann Dunleavy

operated a 10-pin bowling alley. Enos Christman witnessed the

performance of a lady bullfighter. Franklin Buck met a Spanish

(“genuine Castillian”) woman mulepacker. Charlotte

Parkhurst drove a stage for Wells Fargo. Mrs. Raye acted in

the theatre. Mrs. Rowe performed in a circus, riding a trick

pony named Adonis.

And some women danced, some sang, some played musical instruments,

some dealt cards, some poured drinks. What readily comes to

mind with the subject of gold rush women are these saloon girls

and parlor house madams. And who were these so-called soiled

doves? They were Chilean, Mexican, Chinese, French, English,

Irish, and American. No stereotype encompasses them all, for

they and their experiences were as diverse as the population.

A few were phenomenally successful, most merely survived. Despite

popular 19th century assumption that women were driven into

prostitution by seduction and abandonment, most pursued the

profession for economic reasons.

Among the first, believed to have arrived in San Francisco in

1849, was a Chinese woman named Ah Toy. She was a ‘daughter

of joy,’ the Chinese expression for prostitute, but she

was more than that. She was an extraordinary woman. First, she

was independent of any man, Chinese or Caucasian, remarkable

for an Asian woman. Second, she spoke English, also most unusual

for a Chinese woman. Third, she was assertive and intelligent,

for she quickly learned to use the American judicial system,

regularly taking her grievances to court.

Obviously, she was adventurous, determined, hardworking, bright,

independent, aggressive—the very qualities of a successful

49er.

She shared those qualities with thousands of pioneering women

who demonstrated the courage and determination required by the

unique circumstances of gold rush California.

And yet when most people think about 49ers, they think of them

as men. And yet, women – women with gold fever like Louisiana

Strentzel, suffering overlanders like Sarah Royce and Juliet

Brier and Catherine Haun, the boardinghouse keepers like Mary

Ballou and Luzena Wilson and Mary Jane Megquier, potato growers

like Eliza Farnham, the pie makers, the washerwomen, the seamstresses,

prostitutes, actresses, circus riders, nurses, teachers, wives,

mothers, sisters, and daughters – women were 49ers, too.

To Learn more about

the author and her books click on a book below...

About the

Author

JoAnn Levy has been writing about California’s gold-rushing

women for more than twenty years and is the author of the now-classic

They Saw the Elephant: Women in the California Gold Rush. Her

first fiction, Daughter of Joy, A Novel of Gold Rush San Francisco,

won the 1999 Willa Award for Best Historical Fiction. A second

novel, For California’s Gold, captured the prize in 2001,

after debuting at the National Archives in Washington, D.C.,

where Levy spoke in honor of Women’s History Month and

California’s statehood sesquicentennial.

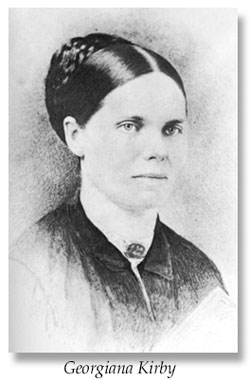

Just released is a “biographical gem,” Unsettling

the West: Eliza Farnham and Georgiana Bruce Kirby in Frontier

California, in which Levy recounts the lives and adventures

of two remarkable women, pioneer reformers who touched history

and made history.

A frequent speaker on behalf of the gold-rushing women she discovered

in nearly a decade of research, Levy has been featured in numerous

TV documentaries.

Visit JoAnn's webstie at: http://www.goldrush.com/~joann/index.html

Unruh, John D., Jr., The Plains

Across (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1982), p. 85.

Holliday, J. S., Rush for Riches (Berkeley: University of California

Press, 1999), p. 94.

Megquier, Mary Jane, Apron Full of Gold: The Letters of Mary

Jane Megquier from San Francisco, 1849-1856, ed. Robert Glass

Cleland (San Marino, Calif.: Huntington Library, 1949), Letter

dated Panama, May 14, 1849.

Ibid., Letter dated November 4, 1855. Brown, Lucilla Linn, “Pioneer

Letters,” ed. Gaylord A. Beaman, Historical Society of

Southern California Quarterly (March 1939), pp. 18-26. Haun,

Catherine, “A Woman’s Trip Across the Plains, 1849.”

In Women’s Diaries of the Westward Journey, by Lillian

Schlissel (New York: Schocken Books, 1982), p. 170. Strentzel,

Louisiana, “Letter from San Diego, 1849.” In Covered

Wagon Women, Vol. 1, ed. Kenneth L. Holmes (Glendale, Calif.:

Arthur H. Clark Co., 1983), p. 250. Ward, Harriet S., Prairie

Schooner Lady: The Journal of Harriet Sherrill Ward, 1853, eds.

Ward G. and Florence Stark DeWitt (Los Angeles: Westernlore

Press, 1959), p. 132. Parsons, Lucena, “The Journal of

Lucena Parsons.” In Covered Wagon Women, Vol. 2, ed. Kenneth

L. Holmes (Glendale, Calif.: Arthur H. Clark Co., 1983), p.

247. Hester, Sallie, “The Diary of a Pioneer Girl.”

In Covered Wagon Women, Vol. 1, ed. Kenneth L. Holmes (Glendale,

Calif.: Arthur H. Clark Co., 1983), p. 244. Royce, Sarah, A

Frontier Lady: Recollections of the Gold Rush and Early California

(New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1977), p. 248. Haun,

op. cit., p. 182. Journals of Forty-Niners: Salt Lake to Los

Angeles, ed. LeRoy R. and Ann W. Hafen (Glendale, Calif.: The

Arthur H. Clark Co., 1954), p. 38. Wheat, Carl I., “The

Forty-Niners in Death Valley: A Tentative Census,” Historical

Society of Southern California Quarterly, December 1939. Belden,

L. Burr, Death Valley Heroine: And Source Accounts of the 1849

Travelers (San Bernardino, Calif.: Inland Printing & Engraving

Co., 1954), p. 21ff. Ibid., p. 27. Latta, Frank, Death Valley

‘49ers (Santa Cruz, Calif.: Bear State Books, 1979), p.

200. Ibid., p. 306. Ibid., p. 260. Booth, Anne Willson, “Journal

of a Voyage from Baltimore to San Francisco…, 1849.”

Ms. diary, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley,

p. 234. Mrs. John Berry, “A Letter from the Mines,”

California Historical Society Quarterly, Vol. V (1927), p. 293.

“Reminiscence of San Francisco, in 1850,” by Francesca,

in The Pioneer, ed. F. C. Ewer, Vol. 1, January 1854. Farnham,

Eliza W., California In-Doors and Out (New York: Dix, Edwards

& Co., 1856), p. 42. Ibid., p. 56. Ibid., p. 107. Alta California,

December 14, 1850. Clappe, Louise Amelia Knapp Smith, The Shirley

Letters from the California Mines, 1851-1852, ed. Marlene Smith-Baranzini

(Berkeley: Heyday Books), p. 68. Mansur, Abby. “Ms. Letters

Written to Her Sister, 1852-1854,” in Let Them Speak for

Themselves: Women in the American West 1849-1900 ed. Christiane

Fischer (Hamden, Conn.: Archon Books, 1977), p. 56. Caples,

Mrs. James. “Overland Journey to California,” unpublished

ms., California State Library, Sacramento. California Emigrant

Letters, ed. Walker D. Wyman (New York: Bookman Associates,

1971), p. 149. Letter to Catherine Oliver, 1850. Manuscripts

collection, California Historical Society, San Francisco. California

Emigrant Letters, op.cit., p. 147. Wilson, Luzena, Luzena Stanley

Wilson, ‘49er (Oakland: The Eucalyptus Press, Mills College,

1937), p. 27. Megquier, op.cit., Letter dated June 30, 1850.

Ballou, Mary B., “I Hear the Hogs in My Kitchen –

A Woman’s View of the Gold Rush” in Let Them Speak

for Themselves: Women in the American West 1849-1900 ed. Christiane

Fischer (Hamden, Conn.: Archon Books, 1977), p. 43. Quoted in:

Jackson, Joseph H., Anybody’s Gold: The Story of California’s

Mining Towns (New York: D. Appleton-Century Co., 1941), p. 101.

Gagey, Edmond M., The San Francisco Stage: A History (New York:

Columbia University Press, 1950), p. 38. Alta California, April

3, 1851. Alta California, January 29, 1850. Eastman, Sophia,

Letters. Maria M. Eastman Child Collection, The Bancroft Library,

University of California, Berkeley. Farnham, op.cit., 275. Ferguson,

Charles D., California Gold Fields (Oakland: Biobooks, 1948),

p. 103. Comstock, David A., Gold Diggers & Camp Followers:

The Nevada County Chronicles 1845-1851 (Grass Valley, Calif.:

Comstock Bonanza Press, 1982), p. 322. Christman, Enos, One

Man’s Gold: The Letters & Journal of a Forty-Niner,

ed. Florence Morrow Christman (New York: McGraw-Hill Book Co.,

1930), p. 198. Buck, Franklin A., A Yankee Trader in the Gold

Rush (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1930), p. 126. Curtis, Mabel

Rowe, The Coachman Was a Lady (Watsonville, Calif.: The Pajaro

Valley Historical Association, n.d.). Davis, W. N., Jr., “Research

Uses of County Court Records, 1850-1879, And Incidental Intimate

Glimpses of California Life and Society,” California Historical

Quarterly Vol. LII, No. 3, p. 255. Rowe, Joseph A., California’s

Pioneer Circus: Memoirs and Personal Correspondence Relative

to the Circus Business Through the Gold Country in the ‘50s,

ed. Albert Dressler (San Francisco: H. S. Crocker Co., 1926).

Sanger, William W., M.D., The History of Prostitution (New York:

Eugenics Publishing Co., 1937), p. 488. Alta California, March

6, 8, 1851; July 1, 1851; December 14, 24, 1851; December 11,

1852

One

of them was Mary Jane Megquier who crossed the Isthmus early

in 1849, and wrote this of her Chagres River journey:

One

of them was Mary Jane Megquier who crossed the Isthmus early

in 1849, and wrote this of her Chagres River journey:

Lucena’s

journal was not otherwise a happy record. Lucena was a grave

counter. Few of her journal entries failed to mention at least

one. In all, she counted more than 380 graves while crossing

the plains. So commonplace was the face of death by the time

her party reached Fort Laramie that she sandwiches mention of

it casually between other observations:

Lucena’s

journal was not otherwise a happy record. Lucena was a grave

counter. Few of her journal entries failed to mention at least

one. In all, she counted more than 380 graves while crossing

the plains. So commonplace was the face of death by the time

her party reached Fort Laramie that she sandwiches mention of

it casually between other observations:

When

one young man suggested to Juliet that she and her children

remain behind and let them send back for her, she adamantly

refused:

When

one young man suggested to Juliet that she and her children

remain behind and let them send back for her, she adamantly

refused: Care

for her own family consumed most of Juliet’s strength.

In one 48-hour stretch without water, her oldest boy Kirk suffered

terribly:

Care

for her own family consumed most of Juliet’s strength.

In one 48-hour stretch without water, her oldest boy Kirk suffered

terribly: Forty-niner

Anne Booth came around the Horn in a ship she continued to live

aboard for more than a month in San Francisco’s Bay, and

wrote:

Forty-niner

Anne Booth came around the Horn in a ship she continued to live

aboard for more than a month in San Francisco’s Bay, and

wrote: A

reminiscence of a lady guest from those early days confirms

that her bed there was “delightful.” Two “soft

hair mattresses” and “a pile of snowy blankets”

hastened her slumbers, which were soon interrupted:

A

reminiscence of a lady guest from those early days confirms

that her bed there was “delightful.” Two “soft

hair mattresses” and “a pile of snowy blankets”

hastened her slumbers, which were soon interrupted:  Not

afraid of labor, Mrs. Farnham set herself the task of building

a new house:

Not

afraid of labor, Mrs. Farnham set herself the task of building

a new house: